The Role of Music Keepsakes in Parasocial Attachment and Grief

Author(s): Lauren Alex O’Hagan

27/01/2025I still remember exactly where I was when I heard the news that Tom Petty, one of my favourite musicians, had passed away. Gone were my opportunities to ever see him in concert or meet him backstage. I felt numb, realising that I had nothing to remember him by and I spent months in disbelief, struggling to make sense of the loss. This made me reflect on how having such experiences—and the objects associated with them—might have helped me better process my parasocial grief, defined by Cohen and Hoffner as the grief felt after the death of a beloved public figure.

My Open Societal Challenge explores exactly that: how fans navigate death and memorialise life through objects received from encounters with their musical icons, and how the meaning of these objects evolves after the musician’s passing. I use the Irish blues musician, Rory Gallagher, as my case study, conducting object-oriented interviews with fans from across the world, contacted through Facebook fan groups. Through a multimodal ethnographic approach, I examine the objects’ entangled relationships with people, places and memories, their broader historical and sociocultural significance, their location within the home and their shifting values over time.

Although I am in the early stages of this research—having just completed the interviews and preparing to begin thematic analysis—it is already clear that these objects hold an extraordinary place in people's hearts, and indeed, homes.

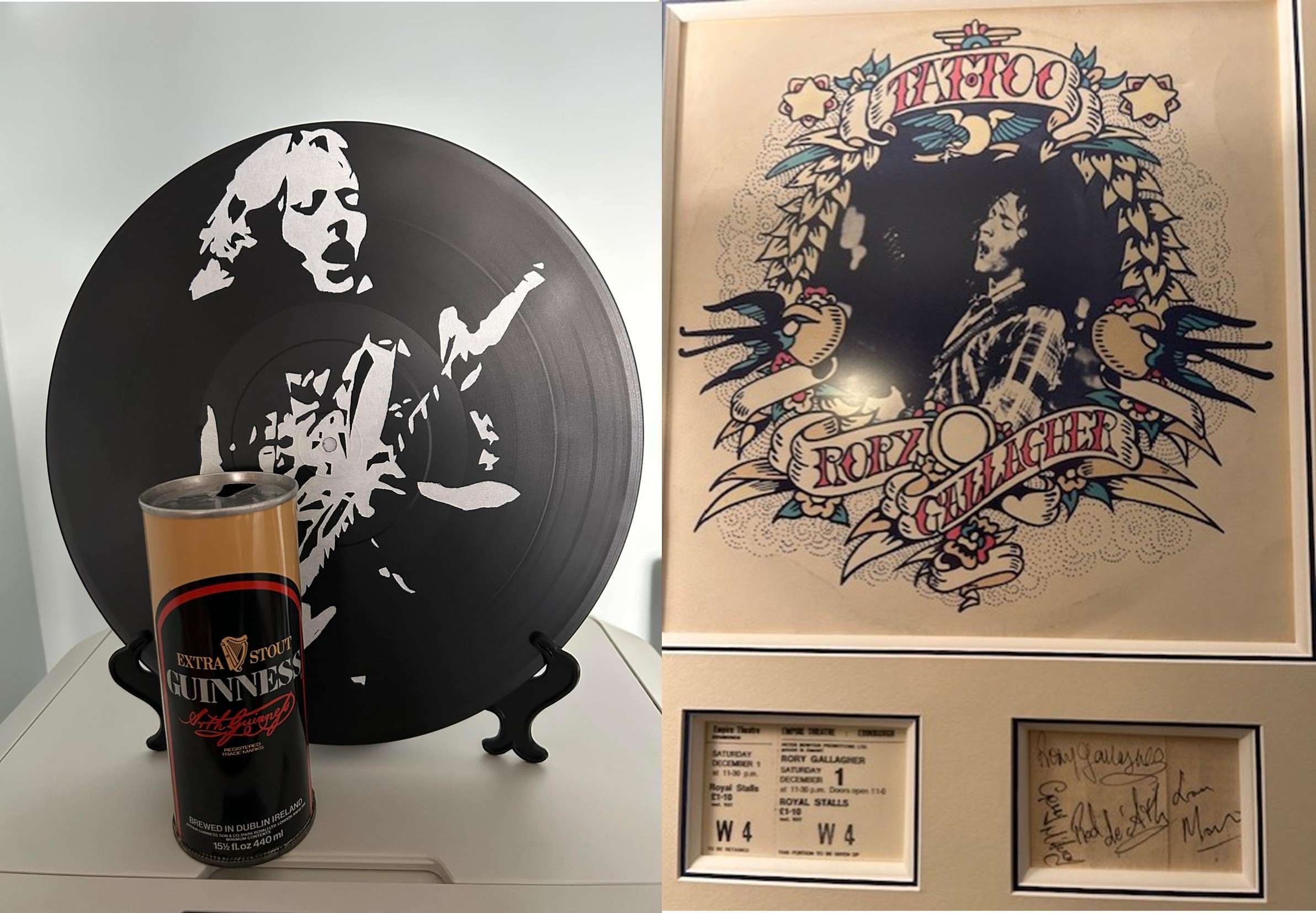

Take Tom, for example, who, for over 50 years, has kept a Guinness can given to him by Rory backstage at the Edinburgh Empire Theatre. It holds pride of place in the music room of his home, forming what he describes as a “unique piece of artwork” alongside a vinyl disc featuring Rory’s silhouette, a framed copy of Tattoo, his concert ticket and autographs from Rory and the band. The room serves as a sanctuary for him, where:

“I just go in, see the objects and they evoke all these memories of the past and make me want to sit down and play Rory Gallagher […] I don’t know if adoration is too strong a word, but I suppose it is in a way. I just feel so blessed to have been able to attend his concerts and spend time with him giving me such precious memories which are still as vivid today after all these years.”

Image: The Rory Gallagher display in Tom’s music room

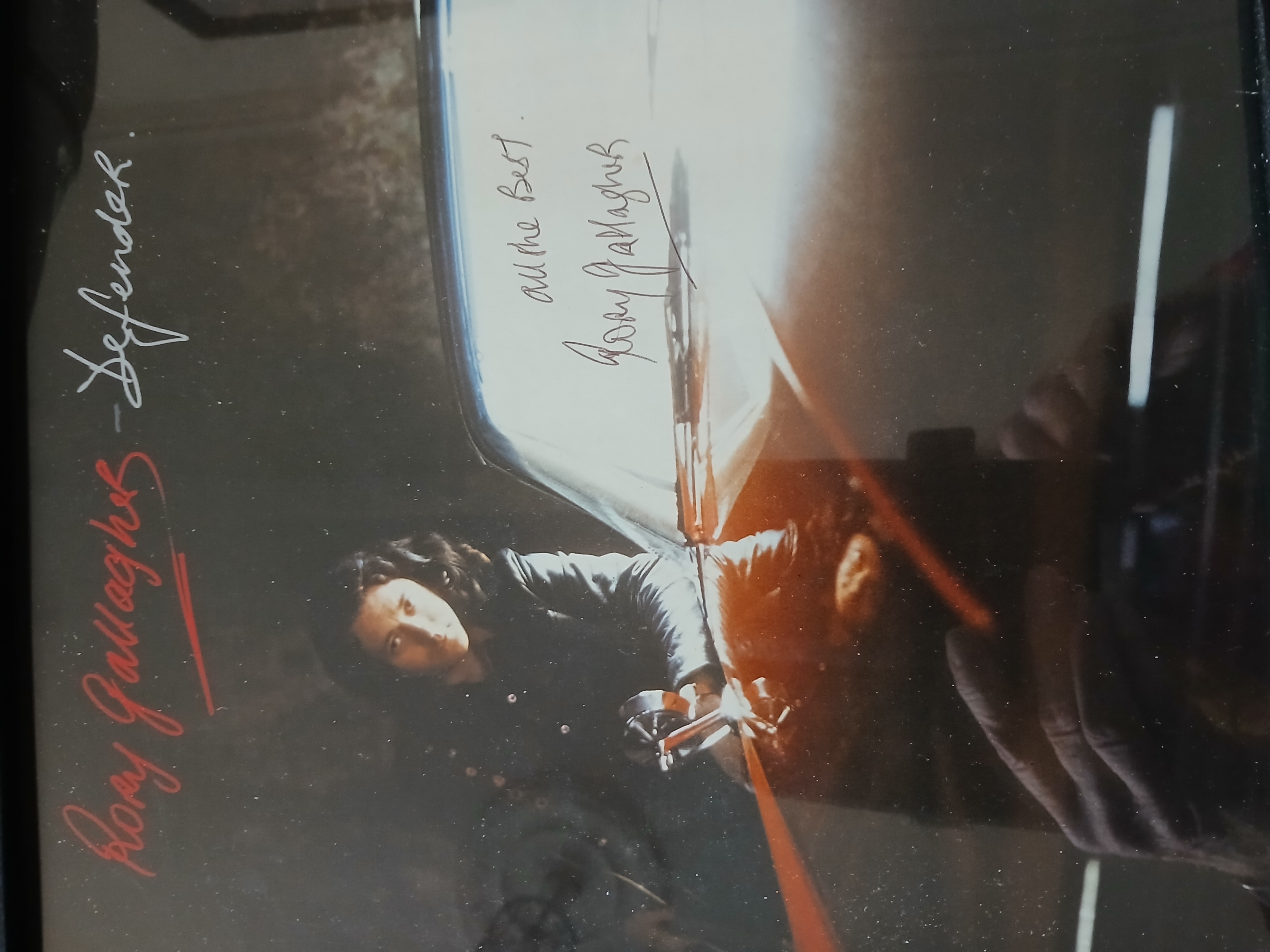

For David, who met Rory backstage in 1990 at the Manchester International 2 and had several LPs signed and photographs taken, these items have become “treasured possessions” that have only deepened in significance since Rory’s untimely passing in 1995:

“[When Rory died], it was almost like a family member had died. I thought, ‘I can’t believe I’m not gonna see him again’. So, they just remind me that from 1973 onwards, I’ve had Rory in my life. I’ve had the privilege to have seen him and enjoy his music. They make me think of when I was young and Rory was still here. And these are items that he’s actually touched, you know, which makes them absolutely priceless”

Image: David’s signed copy of ‘Defender’

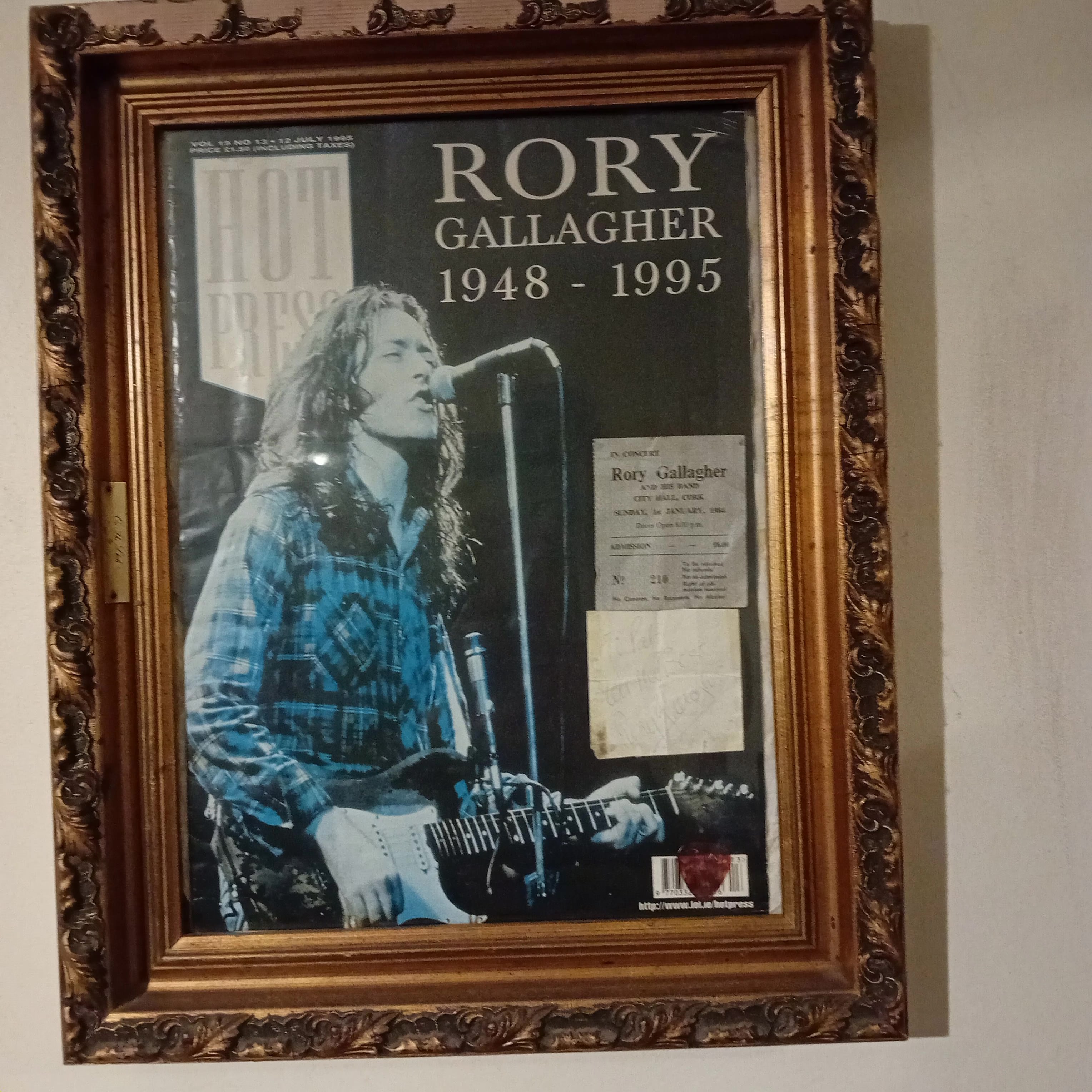

Pat, who cheekily asked Rory for his plectrum when they met in 1988 backstage at Cork City Hall, originally kept the item in a small box with other keepsakes. However, after Rory’s death, the plectrum was elevated:

“Hot Press [magazine] did a special issue after Rory died. I remember we were living in this crummy tenement flat and up on the wall they had the old Sacred Heart painting. So, I cut off the cover of Hot Press, ripped out the Sacred Heart, chucked it away and put in Rory with the concert ticket, autograph and plectrum! That hasn’t changed since 1995.”

Image: Pat’s Rory Gallagher tribute

Such powerful stories have made me think more broadly about a bottom-up approach to the material culture of music and how objects carry a certain ‘aura’, serving as gateways to rich narratives about musical memories, nostalgia, youth, identity and relationships. In the coming year, I will explore this idea further with a visit to the Oh Yeah! Music Centre in Belfast, which holds a collection of scrapbooks created in the 1970s by a teenage Rory fan. This visit will lay the foundation for a funding application focused on the live music scene during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, exploring resilience, sense-making and webs of memories through music memorabilia.

If you’d like to read more about the project, visit: https://rewritingrory.co.uk/2021/11/11/projects/.

The project can also be reached via the Challenge page.

Dr Lauren Alex O’Hagan is Research Fellow in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at the Open University and Affiliate Researcher in the Department of Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University. She specialises in the study of visual and material culture across a range of historical periods, geographical settings and subjects. She has published extensively on the Irish blues musician, Rory Gallagher, running the website Rewriting Rory (www.rewritingrory.co.uk) and co-authoring Rory Gallagher: The Later Years (Wymer, 2024), which fosters a reappraisal of the final decade of his career.